Imagine the Next Normal -- Health Equity

Part #5 in a series focused on creating healthier and safer communities for all

I am pushing back HARD against the desire to return to normal.

Instead of wanting to return to what was pre-COVID, I am stepping into the future — the NEXT NORMAL — with the hope that we can create healthier and safer communities for all. Returning to 2019 normal is unacceptable. PERIOD. It is unacceptable because we have all changed, grown, and learned so much living through (read: surviving) a pandemic.

I invite you to explore this NEXT NORMAL with me in this 10-part blog series (yes, I am fired up, inspired, and really excited). If you are jumping in today, please go back and read my inspiration for the series as well as my posts on physical health & access to healthcare, mental health, social & emotional health, and community health.

When I was putting together this series on imagining our next normal, I was very intentional about my decision to discuss community health before health equity - because we cannot talk about racism and health without understanding the forces at work in our communities that contribute to our ability (individually or collectively) to be healthy. We cannot understand health disparities1 (health differences that are closely linked with economic, social, racial, and environmental disadvantage) and the need for health equity (when everyone has fair access and opportunities to achieve optimal health and no one is denied those opportunities because of socially determined circumstances) without understanding the importance of healthy communities.

The SARS-CoV-2 does not discriminate based on race or socioeconomic status.

“And yet, from the very beginning of the pandemic, the virus has exposed and targeted all of the disparities that come along with being Black in America.” ~Patrice Peck

According to the COVID Tracking Project, the COVID mortality rate among Black people in America is 1.4 times higher than that of White people.

And according to Dr. Ibram Kendi —

“To explain the disparities in mortality rates, too many politicians and commentators are noting that Black people have more underlying medical conditions, but crucially, they’re not explaining why.”

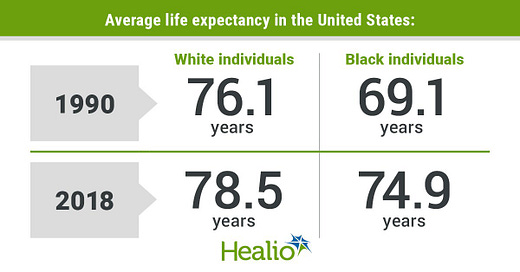

Why do Black Americans have more underlying health conditions than White Americans? Why is the average life expectancy higher for White Americans compared to Blacks?

Why do these differences exist?

According to an article published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine —

“A prominent scholar of health disparities reports that this ‘strikingly excessive rate,’ often misattributed to putative biologic or genetic differences between Black and White bodies, must be understood as a spotlight illuminating the fundamental racial inequities in American society. This structural impact of race and racism as social determinants of health, rather than any biology of racial difference, confers on Black Americans a higher risk of getting sick and lower chances of having access to or adequate service from the health care system.”

What may surprise you about this quote is that it was not written in reference to life expectancy or to COVID mortality. It was written in 1899 by W.E.B. Du Bois, who conducted years of demographic, ethnographic, and sociological research in an effort to show that racism and segregation were the root cause of Black people dying from tuberculosis more frequently than White people in Philadelphia in the 1890s (source — The Philadelphia Negro).

What Du Bois recognized in the 1890s still holds true today —

“Underlying health conditions (increased mortality and a shorter life expectancy) are rooted in years of systematic racism.” ~Dr. Ibram Kendi

In 2022 — we are facing BOTH a viral pandemic as well as a racial pandemic.

And conversations about our next normal MUST include racism, sexism, ableism, and the underlying social forces and power structures that are impacting the health of individuals and groups.

When health disparities are identified, we cannot simply say we do not understand why those disparities exist. We must ask WHY do health disparities exist.

And the public health workforce needs to give up its hold on being the only authority able to conduct research and introduce policies, programs, and interventions to improve the health of our communities. We need to look to our friends in history, sociology, psychology, demography, Black studies, religious studies, ethics, gender studies, and beyond to help us understand the WHY — why do health disparities exist? why is a White man expected to live longer than a Black man? why are Black people dying more frequently than White people? why do Black people have more underlying conditions than White people?

In our next normal, I want us all to hear the call of W.E.B. Du Bois, who worked to —

“shift the goals of social analysis away from blaming social ills on individuals or groups toward a richer understanding of the ways in which power relations shape life and health outcomes.” ~NEJM

Our understanding of health — healthy individuals and healthy communities — must include conversations, research, policies, programs, and education about racism (as well as ableism, sexism, patriarchy, and poverty).

We CAN NOT be satisfied with just the knowledge that one group of individuals is healthier than another group.

We CAN NOT allow public health researchers to just say group A has a higher risk of mortality than group B. And then be comfortable with their work stopping there.

We MUST collaborate across disciplines to understand why health disparities exist and what is necessary to ensure health equity — when differences between groups no longer exist.

We MUST advocate for health equity.

And for those of us, myself included, who do not face racism and health disparities on a daily basis, we need to educate ourselves. I want to encourage everyone who is White and reading this to check out these two amazing Black leaders, whose work needs to be elevated and supported —

Dr. Lisa Cooper MD MPH — Her recently published book Why Are Health Disparities Everyone’s Problem is not only a page-turner but a must-read (if you are local and want to borrow my copy, let me know). You can also learn more about the book on the Public Health On-Call podcast #426. The thesis of Dr. Cooper’s work is that there is an “essential need for societies to achieve not just health equity but social justice as well.” She illustrates with brilliant writing and a whole lot of research that we cannot be truly healthy until everyone in our community (local and global) is healthy.

Nicholas St. Fleur, a journalist for STAT News and the host of the new podcast Color Code. The podcast is brand new (only one episode as of today). Episodes cover topics at the intersection of race and medicine. The podcast aims to illuminate the history of racism in health care, how it continues to impact people of color, and what needs to be done to create an equitable system.

Understanding that health disparities exist is essential to creating healthy communities. But we also must seek to achieve health equity, which means we must do the work necessary to understand and provide each individual or group with what they need in order to lead their healthiest lives.

Healthy people need to live in healthy communities. And communities are only truly healthy when everyone is healthy and disparities do not exist.

The work that we have ahead of us — to achieve health equity — involves each of us. And according to (the former) US Surgeon General Dr. David Satcher —

“We can achieve health equity in America, but first, we all must case enough, know enough, do enough, and persist long enough.”

We are all public health. The work to achieve health equity involves all of us.

HHS Secretary Margaret Heckler is responsible for bringing health disparities to the forefront of public health in 1985. Her landmark Heckler Report showed that Blacks and other minorities disproportionately experience more deaths from certain diseases compared to Whites - because of inequalities in health care.